We will be out of office 12/23 - 1/1. Happy Holidays!

Limited Edition: eeBrakes Magnum

Previous slide

Next slide

Cane Creek Cycling Components Brand Manager

Coil shocks have made a resurgence on modern trail bikes within the last few years, and with that comes a question we often hear: should I get a coil shock or an air shock for my full suspension mountain bike?

There will always be exceptions or outliers to these general concepts discussed below- your own personal riding style or preference will also affect the answer to this question.

It’s not the easiest question to answer, but we’ve broken it down into simple, general steps that will hopefully better inform you to make a more educated decision.

A coil shock is linear by nature – it has one constant spring rate – the amount of force required to compress the spring will stay the same as the spring compresses through its stroke. For example, with a 450 lb spring, the force required to compress the spring is 450 lbs per inch through the entire stroke of the spring – this means that if the shock has 2 inches of stroke, the force required to fully compress the spring would be 900lb. – so there is no change in spring rate increase on a coil spring. Coil shocks are generally more sensitive (easier for it to compress and rebound) than their respective air shocks because there are fewer seals in the system, therefore there is less force required to get the shock moving. Because of this, coil shocks tend to provide more traction and a unique feel.

An air shock is progressive by nature – the amount of force required to compress the spring continues to increase as the shock compresses. As an air shock moves through its stroke, the volume in the air spring will decrease, subsequently increasing the shock’s spring rate. Air shocks also have the ability to reduce air volume inside the shock by installing volume reducers. This is separate from simply adding air to the shock, a volume reducer only affects the mid-end of the stroke, and will not affect the spring rate at sag. Because of this, air shocks ramp up more and provide more tuning options than coil shocks.

Knowing the differences between the two shocks is most of the battle. But the bicycle’s linkage design also plays a big role. Essentially there are 3 different behaviors found on frame designs and leverage ratios that you should be aware of when considering which type of shock to purchase for your bicycle.

A leverage ratio is the relationship between a given amount of movement the rear shock moves and how much travel it generates at the rear wheel. For example, if the shock moves 1mm, and the rear wheel moves 3mm as a result, the leverage at that point in travel is 3:1.

It might not be obvious, but your shock’s stroke amount is NOT the amount of travel your bike has.

The leverage ratio dictates how much travel your frame will have given a certain amount of stroke. For example, two bikes using a 210x55mm shock, one has 130mm of rear wheel travel, the other has 150mm of rear wheel travel. This means that the 130mm bike has an average leverage ratio of 2.36:1. Whereas the 150mm bike has an average leverage ratio of 2.72:1. Calculating the average leverage ratio is one thing, but in most cases, the leverage of a bicycle changes throughout the stroke.

This is where the three types of frame behaviors come into consideration.

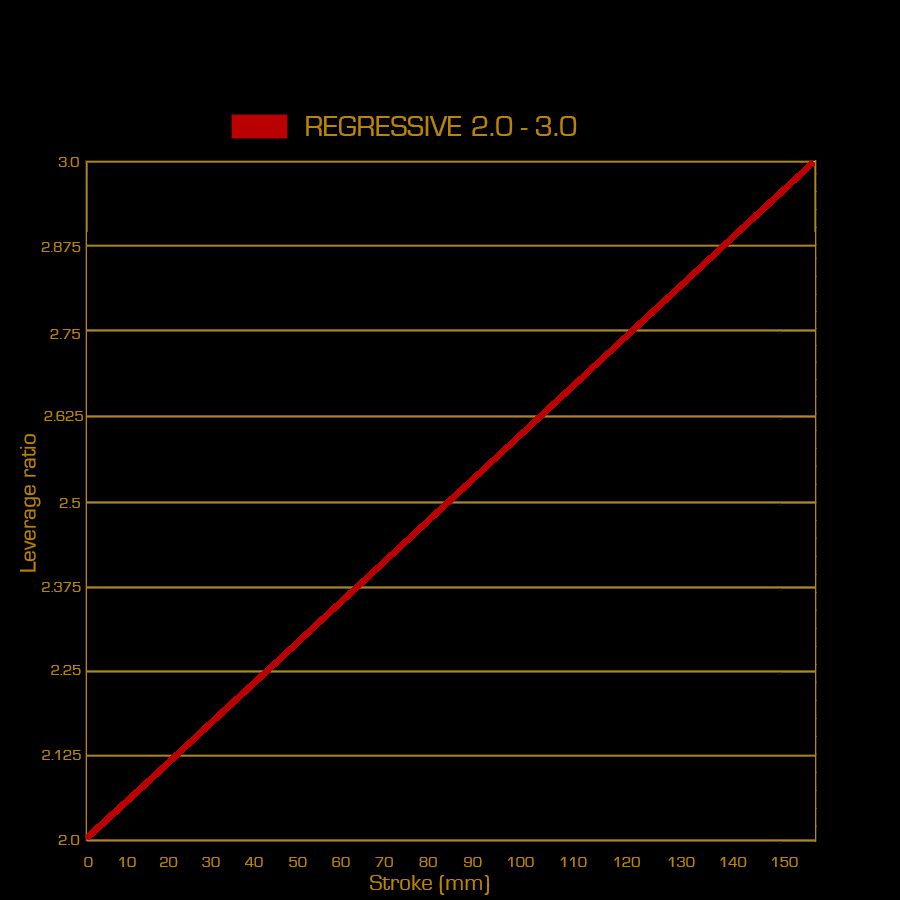

You can evaluate the bike’s leverage ratio curve by plotting those points on a graph. (In most cases, you can find your bike’s specific leverage ratio curve online). Generally, there are three different leverage ratio curves found on modern mountain bikes: Linear, Progressive, and Regressive.

A bike that has an average leverage ratio of 3:1 means that every inch of shock movement equates to three inches of rear wheel movement. As well, this ratio indicates the magnitude of force needed to compress the rear shock. A 150lb rider would need a 450lb spring to achieve proper sag on a bike that has a 3:1 leverage ratio. However, leverage ratios commonly change through the travel of the bike, meaning that our clean 3:1 example will most likely not be 3:1 everywhere in travel, it is only an average based on the overall leverage ratio curve.

When the leverage ratio curve trends down on a graph, it means that the amount of force required to move the rear wheel is increasing. Terms like “ramp-up”, “bottom-out resistance”, and “progression” are used to describe bikes that have a progressive leverage ratio curve. Let’s go back to our example of a 150lb rider using a 450lb spring. If the leverage ratio curve decreases from 3:1 to 2:1, the 450lb spring will continue to feel stiffer throughout the rear wheel travel. In other words, a bike that has a progressive leverage ratio is best for a coil shock.

The “Linear” example above shows a leverage ratio curve that stays the same throughout the entire rear wheel travel. For a bike like this, the frame doesn’t have any progression built in, so if you pair this type of frame with a linear coil shock, the frame’s suspension will not have any progression. In a scenario like this, you could risk a lack of support and harsh bottom-outs. Some bikes have linear natures in certain parts of the leverage curve but also a little bit of progression. In some cases, these types of bikes can be paired with a coil shock if a progressive spring is used.

When the leverage ratio curve trends up on the graph, it means that the amount of force required to move the rear wheel decreases. For this example, the frame’s leverage ratio is 2:1 at the start of travel but increases to 3:1 at the end of travel.

These types of frames are commonly paired with progressive air shocks because the rear suspension design requires the shock to provide ALL of the progressiveness in order to resist bottoming out. Bikes with regressive leverage ratio curves from the beginning to the end of the stroke are uncommon.

It is important to note that most bikes’ leverage ratio curves will change throughout rear wheel travel- but these very simplified graphs are the best way to illustrate these leverage behaviors.

Bikes are generally intended to have bottom-out support, or ramp-up (progressiveness) integrated into the bike’s suspension kinematics so the travel of your bike feels more dynamic and “bottomless.”

So bikes that have progressive leverage ratio curves perform well with coil shocks – because the frame has progression built in. Bikes that have very linear leverage ratio curves perform well with air shocks – because the shock has progressive qualities.

Bikes that have very linear leverage ratios paired with coil shocks are not always ideal because neither the frame nor the shock has progressive qualities. Bikes with progressive leverage ratio curves paired with air shocks can sometimes be too progressive or provide too much ramp-up which could limit the use of travel.

Progressive Frame + Coil Shock = Bike with ramp-up

Linear Frame + Air Shock = Bike with ramp-up

Regressive Frame + Air Shock with Volume Reducers = Bike with ramp-up

These are simple examples of why certain bikes are built with a coil shock or an air shock. But this is where our individual riding styles take over.

If you are a rider that likes to stay on the ground and easily ride over rough terrain with soft supple suspension, then bottom-out resistance may not be important to you. In this case, a coil shock paired with a linear frame would likely not have as many downsides. But if you are a rider that is constantly looking for opportunities to hit the biggest gap or highest drop, bottom-out resistance is far more important. In this case, it is not advisable to pair a coil shock with a linear leverage curve bike, as an air shock would be best to support this riding style and that style of leverage curve.

BUT WAIT.

What if you could get the same progressive benefits that air shocks have while still maintaining the sensitive off-the-top feel of coil shocks?

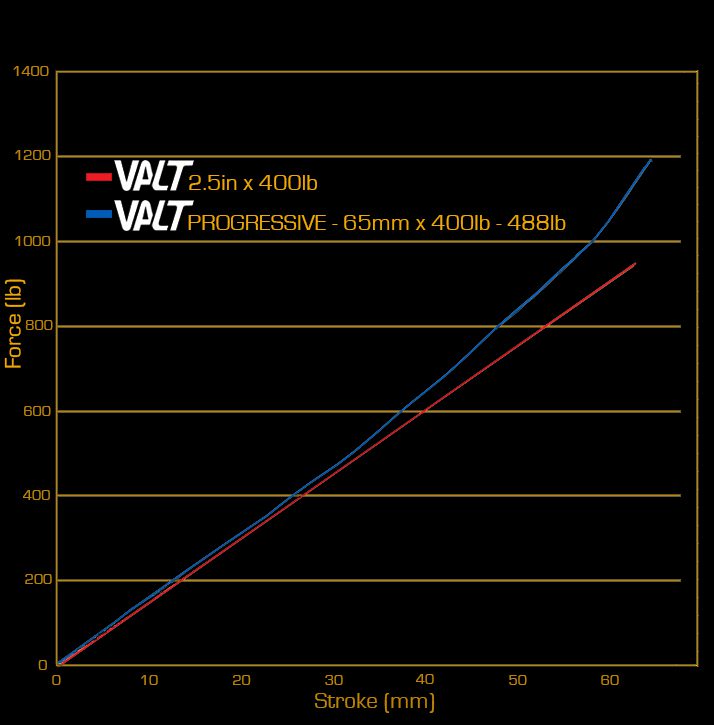

Cane Creek’s new Progressive-Rate VALT spring can offer riders an option to use a coil shock on a bike that might not have been ideal for coil shocks in the past. Because of the lack of a ramp-up, a traditional coil spring has certain frames that bottom out easily.

We have worked to bridge this gap with our new Progressive-Rate VALT springs which are designed and tuned by our engineering team to provide riders with a true rise-in-rate spring curve.

Our Progressive-Rate VALT springs maintain the off-the-top sensitivity of a traditional coil setup and add the progressiveness and ramp-up usually found in an air spring. Below is a graph comparison between a Linear VALT spring and a Progressive-Rate VALT spring. Why are there odd-looking numbers on our progressive spring rates? Because we have matched the spring rate increase to our 22% progressivity on our DBAIR IL air shock with 1 volume reducer installed!

In the market for new rear suspension? Take a look at our premium shocks:

Monday: 10:00 am – 5:00 pm

Tuesday – Thursday: 10:00 am – 5:00 pm

Friday: 10:00 am – 5:00 pm

Saturday – Sunday: Closed